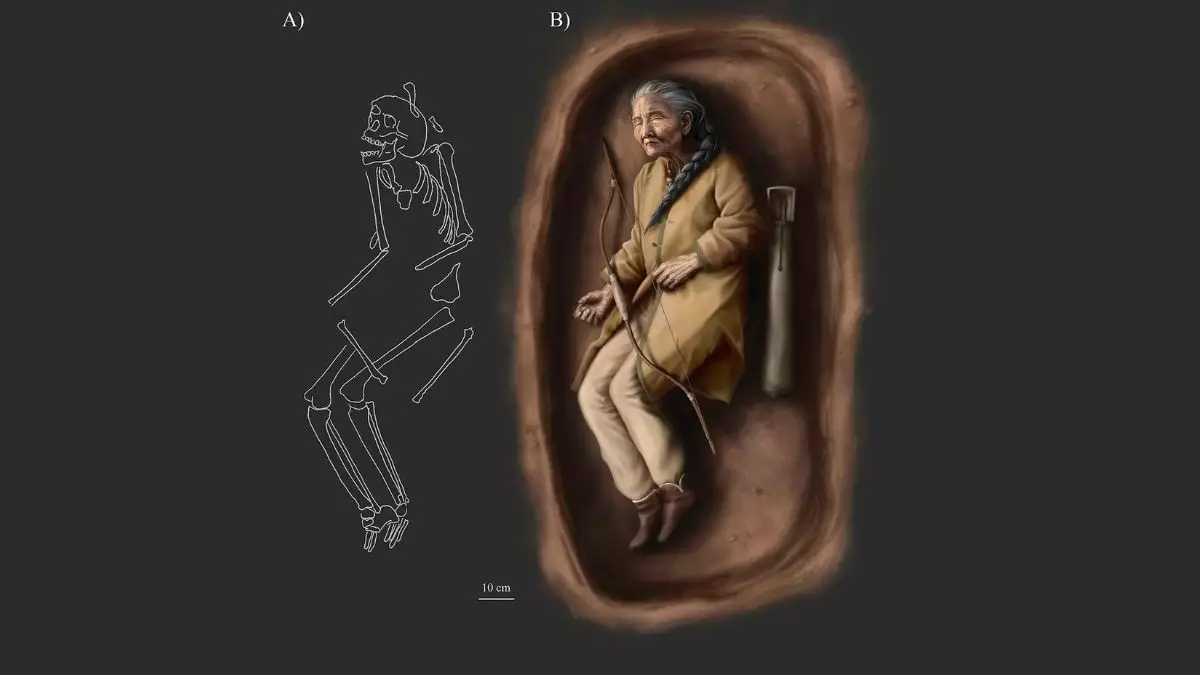

Recent archaeological findings in Hungary have unveiled a groundbreaking aspect of 10th-century burial practices, particularly regarding gender roles. At the Sárréttudvari-Hízóföld cemetery, researchers discovered the skeletal remains of a female, referred to as SH-63, interred with weapons and various grave goods. This finding is considered the first confirmed case of such a female burial in the Carpathian Basin, which challenges long-held beliefs about women’s roles during the turbulent times of the Hungarian Conquest.

Among the items unearthed were a silver penannular hair ring, decorative bell buttons, a bead necklace, and essential archery paraphernalia, such as an arrowhead, quiver parts, and an antler bow plate. The combination of these goods is particularly noteworthy, as it juxtaposes traditional elements associated with femininity alongside more martial artifacts. Dr. Balázs Tihanyi, leading the study published in PLOS ONE, highlighted that this unique blend of grave goods indicates the complexity of identities and roles that women occupied during this era.

Despite the poor condition of the skeletal remains, genetic analyses confirmed SH-63’s gender. However, researchers, including Dr. Tihanyi, caution against jumping to conclusions regarding her status within society. While the presence of archery tools might suggest a life intertwined with warfare, it does not imply that SH-63 was a warrior. Instead, researchers point to the need for comprehensive assessments beyond physical remains. They noted particular markers, such as changes in joints or signs of trauma, commonly linked to horse riding or general robustness, but these could arise from daily activities unrelated to combat. This serves as a reminder that conclusions about social status or roles ought to be established with care.

This discovery raises important questions surrounding gender and social structures in 10th-century Hungary. It underscores potential discrepancies in our understanding of female capabilities and positions in a society historically described as patriarchal. The presence of weapons in a female burial scene suggests that women may have enjoyed more diverse roles than typically acknowledged. Further examination of this site and similar burials from the same period could enrich our comprehension of historical gender dynamics and societal frameworks.

With the confirmation of SH-63’s burial as an outlier among known practices, further studies are set to compare her findings with contemporaneous burials. This could significantly deepen our understanding of 10th-century life and potentially reshape perceptions of women’s roles during the tumultuous Hungarian Conquest era. Through such investigations, historians and archaeologists can unearth a more nuanced picture of a society where diverse identities and roles coexisted, awaiting a closer examination of gender in historical contexts.

Leave a Reply