Music is a unique vessel that transcends temporal and spatial boundaries, conjuring emotions and memories linked to specific places or moments long past. Its role as a cultural touchstone is undeniable. Recent scholarly endeavors have brought to light a fascinating piece of Scotland’s musical history that had remained silent for nearly five centuries. This investigation reveals not only the notes that resonate with historical significance but also enriches our understanding of the liturgical culture prevalent before the Reformation.

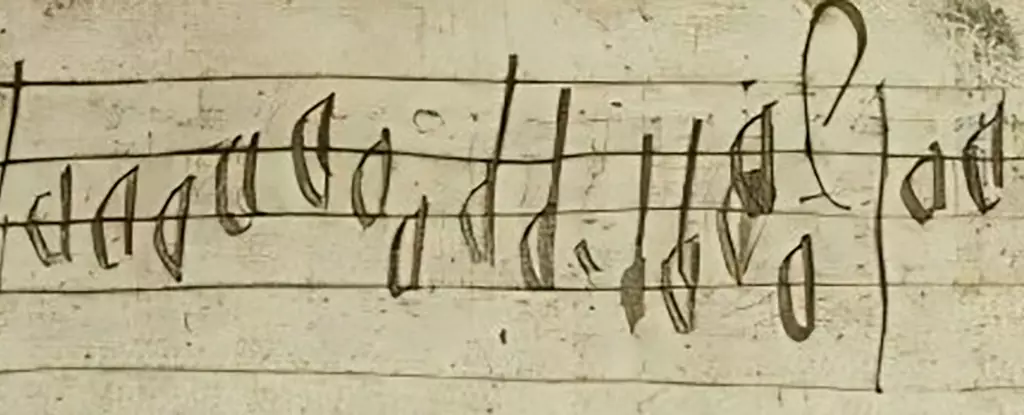

At the heart of this revelation is a 55-note musical fragment unearthed from the margins of the Aberdeen Breviary, a seminal text printed in Scotland in 1510. This compilation primarily consists of prayers, hymns, and readings, solidifying its importance in the annals of Scottish religious literature. The breviary, while a lesser-known work today, serves as a historical benchmark—being the first comprehensive volume to be printed in Scotland. Experts from KU Leuven and the University of Edinburgh meticulously studied this fragment, shedding light on an aspect of Scottish music history that had previously evaded careful examination.

The fragment aligns with an existing hymn called “Cultor Dei, memento,” which is currently recognized as a Christian chant still performed in Anglican churches during Lent. However, the original intent of the notes—whether to guide an instrumental ensemble or a choral arrangement—remains somewhat ambiguous. Nevertheless, the fragment holds profound implications for understanding Scotland’s pre-Reformation liturgical practices, providing a unique auditory insight into the rituals of a bygone era.

The implications of this discovery are underscored by the remarks of musicologist David Coney from the University of Edinburgh, who expressed the significance of resurrecting a hymn that had languished in silence for centuries. The surviving notation comprises a polyphonic work, characterized by multiple independent melodies woven together—an intricate form of musical expression that suggests a rich tradition of multi-voiced singing in Scottish religious settings.

This fragment serves as a compelling counter-narrative to the prevailing notion that pre-Reformation Scotland was devoid of vibrant musical traditions. Musicologist James Cook further emphasizes this by positing that, despite the Reformation upheavals, which eradicated substantial evidence of sacred music, there remained a flourishing culture of musical excellence evident across Scottish ecclesiastical institutions. Such assertions advocate for a reevaluation of historical perspectives regarding music’s development in Scotland.

The broader context of the Aberdeen Breviary’s ownership and provenance also contributes to this narrative. Researchers have traced affiliations with notable sites such as Aberdeen Cathedral and St. Mary’s Chapel in Rattray, Aberdeenshire. Yet, the identity of the individual responsible for inscribing the musical notation remains elusive, hinting at the rich tapestry of collaborative efforts within Scottish liturgical music-making of the time.

This analysis reveals a potent opportunity for further exploration of similar texts. The prospect that more musical insights are hidden within the margins of other 16th-century books suggests that Scotland’s libraries and archives may hold additional treasures yet to be unearthed. This ongoing investigation exemplifies a proactive approach to uncovering the latent history of Scotland’s musical heritage.

As researchers continue to delve into the remnants of history, a broader understanding of Scotland’s musical past emerges. The interdisciplinary collaboration among musicologists not only enhances our appreciation for historical compositions but also ignites curiosity about the often-overlooked cultural practices of past generations. It reinforces the idea that innovation within music is not always tied to new works; instead, it can arise from the rediscovery and revival of ancient melodies ingrained in the collective memory of a society.

The revival of a single musical fragment, long hidden in a historical tome, serves as a beacon revealing the intricate musical landscape of 16th-century Scotland. It prompts contemporary audiences and scholars alike to investigate further, potentially illuminating countless other facets of cultural identity encapsulated within the forgotten pages of history.

Leave a Reply