Despite extensive research into the impacts of antibiotic use on health, particularly in elderly populations, the connection between antibiotics and cognitive decline remains a topic of considerable debate. A recent study led by Dr. Andrew Chan and his team at Harvard Medical School examined this relationship over a follow-up period of nearly five years and found no significant link between antibiotic usage and an increased risk of dementia in a sample of healthy older adults. This finding challenges earlier studies that presented a more cautious outlook on antibiotics concerning cognitive health. However, it is crucial to dissect these results and consider their implications carefully.

Details of the Study: Methodology and Findings

The study, published in the journal Neurology, assessed data from a robust cohort of 13,500 individuals aged 70 and over who participated in the ASPREE trial—a research initiative focusing on aspirin’s effects and its extensions. Participants who did not have significant disabilities or existing health issues at baseline were included, allowing for a clearer assessment of the potential effects of antibiotic use on cognitive health. During the observation period, the research team gathered antibiotic prescription data and conducted comprehensive cognitive assessments at multiple intervals.

Key findings revealed that antibiotic usage did not correlate with a higher incidence of dementia (HR 1.03, 95% CI 0.84-1.25) or cognitive impairment without dementia (HR 1.02, 95% CI 0.94-1.11). Notably, these results were consistent across various antibiotic classes, including those known for penetrating the central nervous system, such as fluoroquinolones and metronidazole. This may suggest a more nuanced understanding of how antibiotics interact with cognitive health than previously thought.

While these findings offer reassurance about the safety of antibiotic use among healthy older adults, the unique characteristics of the study population cannot be overlooked. The participants were predominantly white, with a median age of 75, and came from specific geographical locations in Australia and the U.S. This raises a significant concern about the generalizability of the study’s results. Dr. Wenjie Cai and Dr. Alden Gross from Johns Hopkins University warned that the conclusions may not necessarily extend to the broader elderly population, particularly those with underlying health conditions or varying demographics.

Moreover, earlier studies, such as the Nurses’ Health Study II, have linked extensive antibiotic exposure in midlife to lower cognitive scores years later, contributing to the ongoing confusion surrounding this topic. A clear contradiction arises when early trials suggest potential benefits of antibiotics in certain contexts, such as in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease, contrasting with findings that advocate caution. This landscape creates an intricate tapestry of data that complicates an already convoluted narrative.

The Microbiome Connection: A Double-Edged Sword

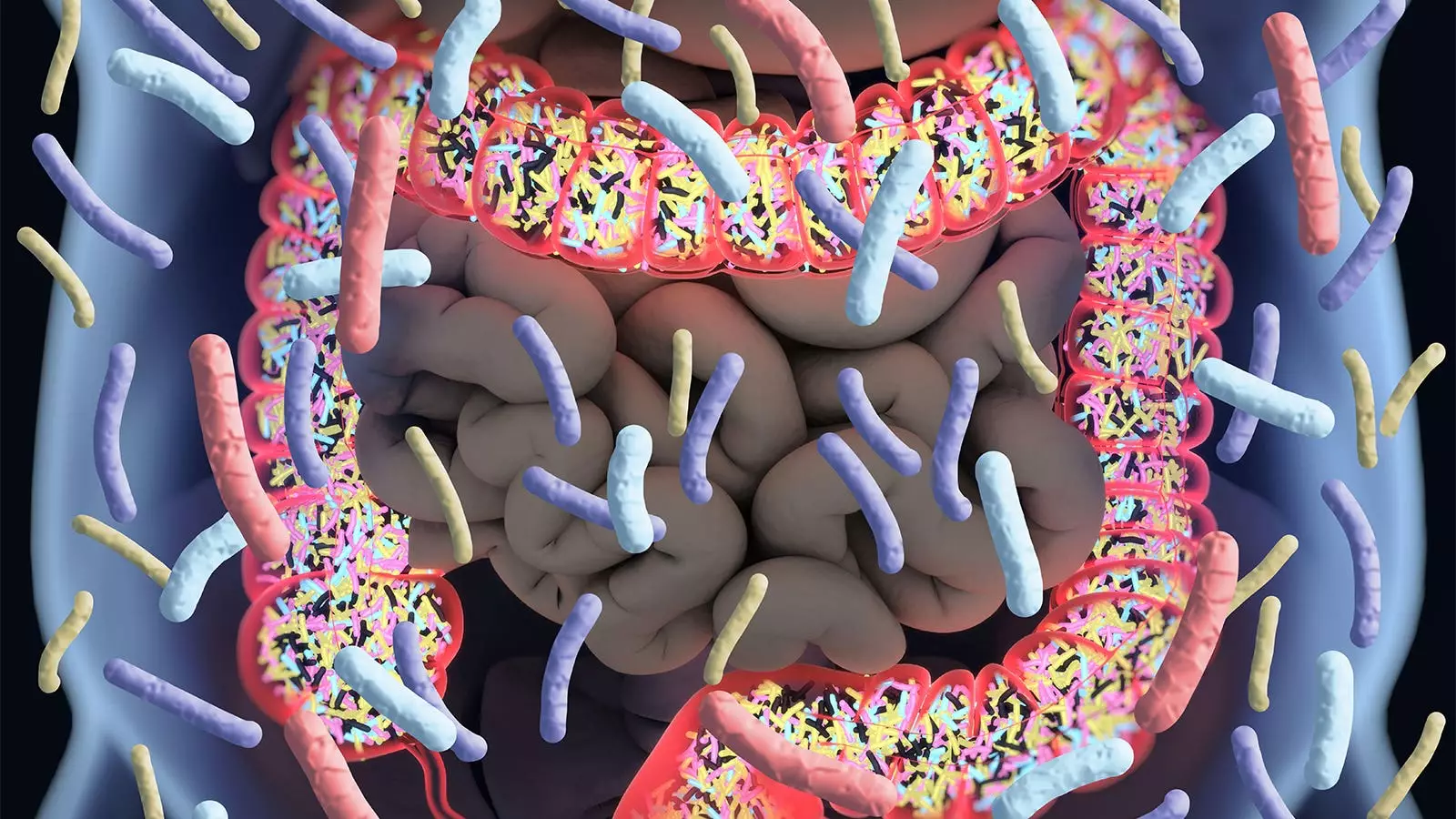

Central to the discussion around antibiotic use and cognitive health is the gut microbiome—a complex ecosystem of bacteria instrumental in various body functions, including metabolism and immune response. Experts like Dr. Chan recognize that antibiotics can disrupt this delicate balance, raising concerns about potential long-term consequences for overall health and cognitive function.

The gut-brain axis, a term that denotes the intricate connection between the gastrointestinal tract and the brain, is gaining attention in scientific research. Disruptions in the microbiome caused by antibiotics could theoretically lead to cognitive issues, yet this study’s reassuring outcomes suggest that, at least in the context of healthy seniors, antibiotics may not exert as significant an impact as once feared.

Nevertheless, it is essential to acknowledge the study’s limitations. The reliance on filled prescription records could skew the data, as these might not reflect actual antibiotic usage. Furthermore, the health status and demographic homogeneity of participants at baseline indicate that different groups, especially those with comorbidities, might not experience the same outcomes. There is still a risk of residual confounding that may have influenced the results, prompting further investigations in varied populations.

Looking ahead, researchers should aim to explore the long-term effects of antibiotics in more diverse demographics and with varying health profiles. Understanding the complexities of antibiotic interactions with the brain may provide insights into preventive strategies against cognitive decline in vulnerable populations.

While the latest findings provide important reassurances regarding antibiotic use in healthy older adults, the broader implications for cognitive health cannot be understated. More research is needed to elucidate potential connections and risks associated with antibiotic use across different populations. As we forge ahead, maintaining a balanced perspective on the benefits and risks associated with antibiotic treatments will be critical for healthcare professionals and patients alike.

Leave a Reply