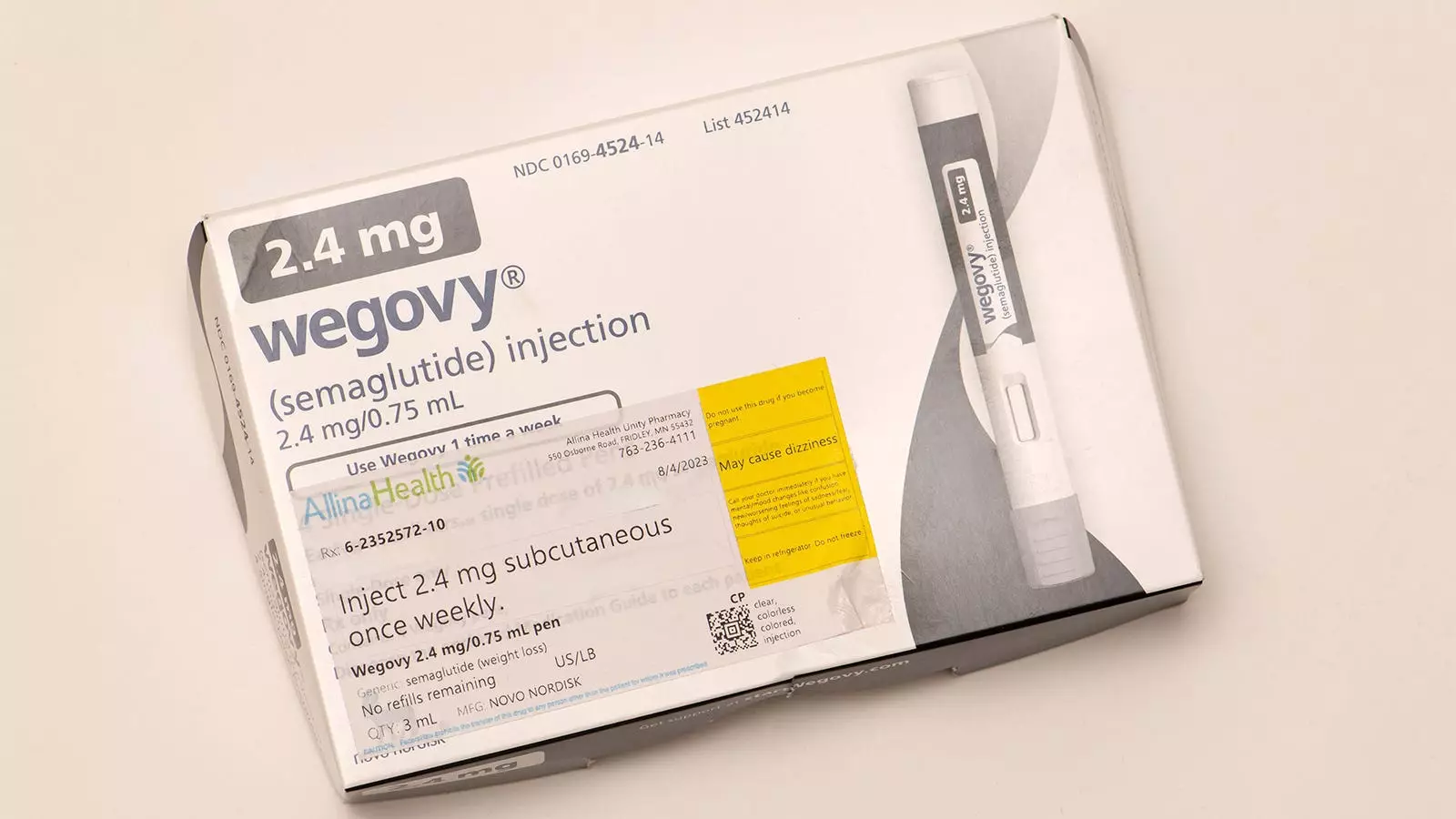

In recent years, childhood obesity has surged to alarming levels, necessitating urgent interventions to manage this complex health issue. The implications of obesity in children extend beyond mere weight gain; they often manifest as severe health complications like diabetes, cardiovascular issues, and psychosocial distress. As a pediatric obesity medicine specialist, I have encountered a myriad of cases involving adolescents grappling with these challenges. One promising avenue in managing adolescent obesity is the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists, specifically semaglutide (commonly known as Wegovy), which, when used alongside comprehensive behavioral lifestyle modifications, has shown positive outcomes in this demographic. For adolescents, these medications can significantly enhance physical activity tolerance, sleep quality, body image, and self-esteem.

However, the situation becomes far more complex when considering younger children—those under the age of 12—who are often confronted with similar obesity-related challenges. Unfortunately, unlike their older counterparts, there are currently no approved pharmacological treatments for this age group to complement lifestyle interventions. This gap in treatment options is now under review, as the FDA has plans to assess the approval of liraglutide for treating severe obesity in children ages 6 to 12.

Recent studies, particularly a randomized trial featured in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), underscore the potential of liraglutide as a complementary therapy for managing obesity in this younger demographic. In a multicenter trial involving 82 children, participants who received a dosage of 3 mg of liraglutide in addition to behavioral interventions over a 56-week period exhibited a notable reduction in BMI by 5.8%. In stark contrast, the group that received behavioral intervention alone saw a 1.6% increase in BMI.

While these findings are encouraging, they also raise several questions regarding the side effects associated with liraglutide. The trial indicated that approximately 80% of the children who received the medication experienced gastrointestinal side effects, although most were categorized as mild to moderate. In comparison, 54% of children in the placebo cohort reported similar effects. This disparity highlights a crucial area of consideration for healthcare providers as they weigh the treatment’s potential advantages against its risks.

The prospect of liraglutide being FDA-approved for young children has significant implications, yet it is essential to approach this development with a critical mindset. The American Academy of Pediatrics has emphasized that medication should only be considered as a supplementary option in conjunction with health behavior interventions for children aged 8 to 11. However, the approval of liraglutide is only the beginning of a more extensive conversation regarding its application.

In evaluating the benefits, there is potential for a modest reduction in BMI and an improvement in specific metabolic and psychosocial risk factors. Although the NEJM trial did not yield statistically significant enhancements in blood pressure or hemoglobin A1c levels, there were observed trends that may suggest emerging benefits in these areas. Notably, research on the physiological and psychosocial impacts of obesity medications in older adolescents has shown positive outcomes, even if such data is lacking for younger children.

Conversely, the risks associated with liraglutide treatment for this age group are of paramount concern. The unknown long-term safety and effects on growth and adult height remain critical unanswered questions. Furthermore, there is a pressing fear that once the medication is discontinued, the weight lost during treatment may be rapidly regained—paralleling the trial outcomes where children on liraglutide regained almost all of their weight within six months of ceasing the treatment.

The management of severe obesity is not a one-size-fits-all approach, particularly in children aged 6-12. While the introduction of GLP-1 medications like liraglutide into treatment options could result in positive outcomes for select patients, health professionals must engage in thorough discussions with caregivers regarding the associated risks and benefits. These medications should never take precedence over the foundational lifestyle interventions that are crucial for fostering long-term healthy habits.

In my practice, the risks of pharmacological intervention generally outweigh the potential benefits for pre-adolescents. However, the availability of liraglutide as an FDA-approved treatment option would represent a significant development and could lead to a re-evaluation of my stance as more research materializes. The ongoing investigation into the long-term safety and efficacy of obesity medications for children is imperative. Moving forward, we must act cautiously and in the best interests of the child while remaining hopeful that advancements in pharmacological treatments will enhance the obesity care landscape for future generations.

Leave a Reply