Cardiovascular disease remains a leading cause of mortality for women worldwide, constituting a significant health crisis that often goes overlooked in public consciousness. When faced with a sudden cardiac arrest, immediate intervention is critical; CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) can greatly increase the chances of survival by ensuring that blood continues to circulate and oxygen reaches vital organs. However, studies suggest a disturbing trend: bystanders appear less inclined to administer CPR to women compared to men. An Australian study conducted between 2017 and 2019 revealed that men received CPR 74% of the time while only 65% of women did. In life-or-death situations, these discrepancies in response can prove detrimental.

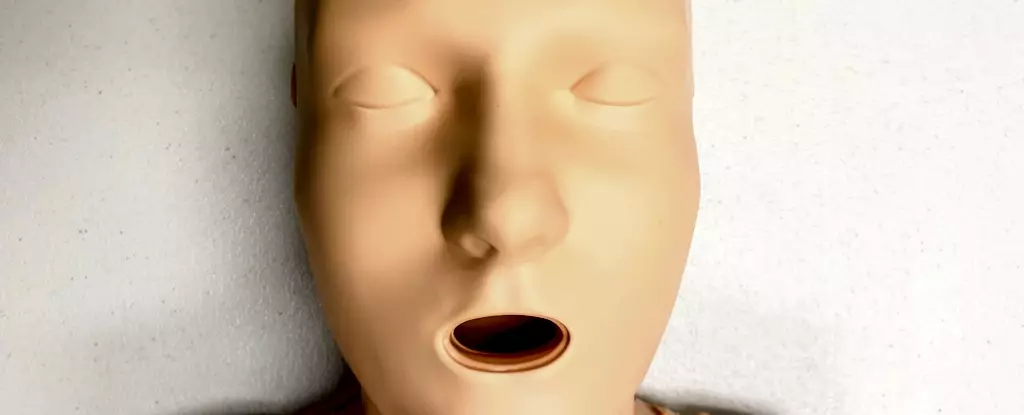

Upon examining the factors contributing to this disparity, one must consider the training tools used to prepare laypeople for emergency situations. Current CPR training manikins are predominantly flat-chested and 95% lack anatomical features that represent women’s bodies. This absence of realistic models can contribute to a subconscious bias, where rescuers may hesitate to act in the moment due to their training experience, which does not accurately reflect real-life scenarios. Indeed, the anatomical differences in human bodies do not change CPR techniques, but they can affect a rescuer’s confidence and willingness to intervene when confronted with a female patient.

Moreover, research has indicated that while CPR techniques remain consistent across genders, the portrayal of victims in training substantially influences bystander behavior. Most available CPR manikins are white, male, and lean, which perpetuates a gendered and biased training paradigm. If all training resources implicitly suggest that CPR is predominantly a male-oriented task, this may lead to hesitation when encountering a female victim in an actual emergency.

The reluctance to perform CPR on women can be attributed to various cultural and psychological factors. Many potential bystanders may hold misconceptions about the physical capabilities of women, viewing them as more “fragile” or requiring gentler treatment. There is also a fear of being accused of inappropriate behavior, especially in scenarios where touching is involved. Studies have shown that bystanders often fail to remove a woman’s clothing necessary for effective resuscitation attempts when the situation arises.

In training simulations in which scenarios mirrored real-life emergencies, researchers found that male participants were less likely to perform life-saving measures on female manikins, even when fully aware of the victim’s dire condition. These insights underline the critical need for addressing these psychological barriers through enhanced training programs that emphasize intervention regardless of gender.

To bridge the existing gap in CPR interventions for women, there is an urgent need for more diverse CPR training manikins that accurately reflect women’s anatomies, including features such as breasts. None of the current manikins on the market fully represent the variety that exists in real life. A 2023 investigation of CPR manikins highlighted that less than 25% were even marketed as female, with only a single model featuring breasts. Moreover, one must question the effectiveness of training resources that lack representation of different body types and racial backgrounds, seeing as these disparities are mirrored in broader health outcomes.

As CPR practices are often informed by previous experiences, training that incorporates a broad spectrum of human bodies can empower students to act confidently and effectively in emergencies. Programs should emphasize the importance of timely intervention, regardless of the victim’s appearance, and ensure that training is inclusive.

In the face of these challenges, it is crucial for individuals to be equipped with the knowledge and skills to take decisive action. Knowing the signs of a cardiac arrest is vital; if an individual is unresponsive and not breathing adequately, immediate CPR might make the difference between life and death. Proper hand placement and rhythm can be achieved without the need for cumbersome clothing adjustments, which should not deter bystanders from initiating CPR.

As a community, we need to instill confidence in people’s ability to respond to someone in need. Comprehensive training that includes diverse representations can lead to a considerable increase in bystander interventions, thus improving survival rates for women experiencing cardiac arrest. It is time we acknowledge and address these critical gaps—not only in awareness but also in education and training—to save lives across genders.

Leave a Reply